Working Capital

Working capital is defined as current assets minus current liabilities. Therefore, a company with current assets of $43,000 and current liabilities of $38,000 has working capital of $5,000.

Current Assets

Current assets are a company’s resources that are expected to be converted to cash within one year of the balance sheet’s date. (However, in industries having operating cycles that are longer than one year, the current assets are the resources that are expected to be converted to cash within the operating cycle.)

Current assets are usually listed in the general ledger and on the balance sheet in the order in which they normally turn into cash. This is referred to as their order of liquidity. The typical order is shown here:

- Cash (currency, checking account balances, money received but not yet deposited, petty cash)

- Cash equivalents

- Temporary investments

- Accounts receivable

- Inventory

- Supplies

- Prepaid expenses

Current Liabilities

Current liabilities are the company’s obligations that will come due for payment within one year of the balance sheet’s date. (In industries with operating cycles that are longer than one year, the current liabilities are the obligations that will come due within the operating cycle.)

Current liabilities are not listed in the order in which they need to be paid. However, it is common to see the current liabilities presented on the balance sheet in the following order:

- Short-term notes payable

- Accounts payable

- Accrued wages and other payroll related expenses

- Other accrued expenses/liabilities (utilities, repairs, interest, etc.)

- Customer deposits

- Deferred revenues

- Others

If a current liability is assured of being replaced with a long-term liability, it should be reported as a long-term liability.

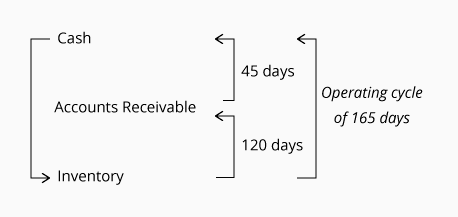

Operating Cycle

If a company sells goods (products, component parts, etc.) its operating cycle is the time it takes for a company’s money to purchase the inventory items and for the money from their sale to return to the company’s checking account.

To illustrate, assume a company purchases goods for inventory and it takes the company 120 days to sell the inventory to customers who are given trade credit terms. Next, assume that the company collects the customers’ money 45 days after the sale. This company’s operating cycle is 165 days as shown here:

Since the operating cycle of 165 days is less than one year, a current asset for this company will be a resource that is expected to turn to cash within one year of the date shown in the heading of the balance sheet. A current liability will be an obligation that is due within one year of the balance sheet’s date (unless there is assurance that the liability will be replaced with a long-term liability).

Liquidity

Liquidity refers to a company’s ability to pay its bills as they come due. In accounting terms, we might say that liquidity is a company’s ability to convert its current assets to cash before the current liabilities must be paid.

Current assets are reported on a company’s balance sheet in their order of liquidity. Since cash is the most liquid asset, it will appear first followed by the current assets that can be quickly turned into cash: cash equivalents, temporary investments, and accounts receivable. The remaining current assets will follow in this order: inventory, supplies, and prepaid expenses.

If a company has most of its current assets in inventory, the company may have a large amount of working capital but may not have the liquidity necessary to pay its current liabilities when they come due. In contrast, another company with a small amount of working capital with little inventory may have the liquidity it needs. (This can occur if a company sells high-demand products through its online website and the customers pay with credit cards when ordering.) Thus, the speed at which a company’s current assets can be converted to cash is as important as the amount of working capital.

A company’s liquidity is also influenced by the credit terms granted by its suppliers. For example, one company may have to pay cash when it receives goods from its suppliers, while another company is permitted to pay 30 or 60 days after receiving the goods. If a company is permitted to pay its suppliers by using its business credit card, it will mean the company’s cash payment can be delayed for 27 to 57 days. With accrual accounting, credit terms and paying with a business credit card will help the company’s liquidity but will not increase the amount of working capital.

Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, a company’s liquidity is affected by the profitability of its business operations. If a company has operating profits because its revenues are greater than its expenses, the company’s working capital and liquidity is more likely to increase. (If the company has operating losses, the company’s liquidity is more likely to decrease.) Operating profits also make it easier for a company to obtain money from long-term lenders or investors in order to increase the company’s working capital and liquidity. On the other hand, operating losses make it difficult to obtain such financing.

Working Capital Ratios

In addition to calculating the amount of working capital (current assets minus current liabilities), there are two financial ratios directly associated with working capital and liquidity:

- Current ratio (sometimes referred to as the working capital ratio)

- Quick ratio (also known as the acid-test ratio)

The current ratio is the total amount of current assets divided by the total amount of current liabilities.

The quick ratio is the amount of “quick” assets divided by the total amount of current liabilities. The quick assets are cash, temporary investments, and accounts receivable.

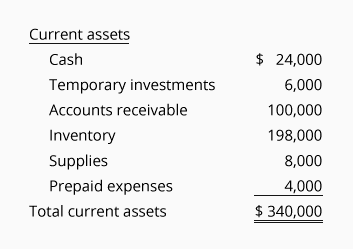

To illustrate the calculations, assume a company has the following current assets:

Also assume that the total amount of the company’s current liabilities is $200,000. Based on our assumptions, the company has the following metrics:

Working capital = $140,000 ($340,000 minus $200,000)

Current ratio = 1.7 to 1 ($340,000 divided by $200,000)

Quick ratio = 0.65 to 1 ($130,000* divided by $200,000)

*The quick assets consist of cash, temporary investments, and accounts receivable

Accounts Receivable

Accounts receivable result from selling goods (or providing services) and allowing the customers to pay at a later date (perhaps in 10, 30, or 60 days). At the time of the sale, the seller transfers ownership of the goods to the customer and in turn becomes one of the customer’s unsecured creditors until the money is collected. This means the seller is at risk for a potential loss if the customer fails to pay. Therefore, it is imperative that the seller be certain that potential and current customers are credit worthy before shipping goods on credit. To avoid the risk of such a loss, the seller could require some of its potential and current customers to pay when the goods are delivered or to pay with a business credit card at the time of delivery.

Accounts Receivable Ratios

There are two ratios/metrics that are calculated for reviewing a company’s success in collecting its accounts receivable:

- Accounts receivable turnover ratio (or receivables turnover ratio)

- Average collection period (or days’ sales in accounts receivable)

The accounts receivable turnover ratio is calculated by dividing a company’s net credit sales for a year by the average balance in accounts receivable during the year.

Outside of your own company, the financial information may not be available. Here are some examples:

- A company may not distribute its financial statements to outsiders

- Only total sales are reported. Credit sales are not listed separately.

- Sales took place throughout the year, but the amount of inventory is the amount at the final moment of the accounting year

- The inventory at the final moment of the year may be much smaller than the inventory throughout the year

To calculate the accounts receivable turnover ratio and the average collection period, let’s assume that in the most recent year all of a company’s sales were credit sales in the amount of $2,000,000 and its accounts receivable had an average balance throughout the year of $250,000. Given these assumptions, the company will have:

Accounts receivable turnover ratio = $2,000,000 of net credit sales divided by the average accounts receivable balance of $250,000 = 8 times.

Average collection period = 360 or 365 days divided by the accounts receivable turnover ratio of 8 times = 45 or 45.6 days.

Inventory

If a company sells goods (products, component parts, etc.), it is common for inventory to be its largest current asset. Having sufficient inventory is necessary to serve and retain customers, but too much inventory can result in excessive expenses (including potential losses if any of the goods become obsolete).

Slow-moving inventory may also cause a liquidity problem since the company’s cash is now sitting in the warehouse as inventory. The inventory needs to be sold for the company to have the cash to pay its current liabilities.

Inventory Ratios

The following ratios are often computed to see how a company has managed its inventory:

- Inventory turnover ratio

- Days’ sales in inventory

The inventory turnover ratio is best calculated by using the following amounts from the most recent year: the cost of goods sold divided by the average balance in inventory. The cost of goods sold is used because typically the inventories are recorded and reported at cost (not at selling prices).

The average inventory amounts during the year are known to people within a company, but outsiders may know only the amount as of the final moment of the accounting year. Since U.S. companies often end their accounting years when their business activity is slowest, the inventory cost reported on their balance sheets may be less than the average of the inventory amounts throughout the year.

To illustrate the inventory ratios, we will assume that a company’s cost of goods sold for the most recent year was $1,440,000 and that the average amount of inventory throughout the same year was $480,000. Given these assumptions, the company will have:

Inventory turnover ratio = the cost of goods sold of $1,440,000 divided by the average inventory of $480,000 = 3 times.

Days’ sales in inventory = 360 or 365 days divided by the inventory turnover ratio which was 3 times = 120 or 121.7 days.

These metrics are averages because sales do not occur evenly throughout the year. In addition, some inventory items may turn over quickly while some items are rarely sold.

Financial Ratios in General

When financial ratios are calculated using the amounts reported on a company’s financial statements, the ratios reflect the transactions that occurred perhaps a year ago. It is possible that today the demand for some products has changed, new competitors entered the market, economic conditions changed, etc.

Financial ratios allow a company to track the trend of its own ratios over several years. It could also be helpful when comparing one company’s financial ratios to those of another company within the same industry. However, the ratios may be of no value when they are compared to the ratios of companies in different industries.

Within a company, the financial ratios based on the prior year’s summarized amounts are less valuable than current, detailed information. For example, the accounts receivable turnover ratio based on last year’s amounts is less valuable/relevant than an aging of today’s accounts receivable. Similarly, an inventory turnover ratio based on last year’s summarized amounts is less valuable than a report comparing the current quantities of every inventory item on hand with the quantity sold in the recent past. This report will expose the inventory items not turning over.

Cash Flow Statement

Since liquidity depends on a company having the cash to pay its obligations when they come due, insights can be guided from reading a company’s statement of cash flows (SCF or cash flow statement). While the SCF may be difficult to prepare, you can read and understand it with a little coaching.

The SCF organizes a company’s main cash inflows and cash outflows into three major sections:

-

Cash flows from operating activities which typically begins with net income (based on the accrual method of accounting) and then lists the adjustments necessary to arrive at the cash from its business operations. The adjustments include the adding back of noncash expenses such as depreciation, and the changes in the working capital accounts (except for short-term loans which are included as part of financing activities).

-

Cash flows from investing activities which includes the purchase and/or sale of long-term assets.

-

Cash flows from financing activities which includes borrowing and/or repaying of short-term and long-term debt, issuing and/or repurchasing of capital stock, declaring of dividends to stockholders, and draws made by an owner.

Cash flows from operating activities

We will focus on the first section of the SCF, cash flows from operating activities, which shows the adjustments made to convert the working capital accounts (except for short-term loans payable). The adjustments involve the changes in the balances at the end of the year minus the balances from one year earlier. Let’s clarify this with some examples using hypothetical amounts:

-

If the balance in accounts receivable was $50,000 at the end of the year and was $38,000 one year earlier, the accounts receivables increased by $12,000. An increase in accounts receivable is not good for the company’s liquidity since less was collected than was sold. Since this increase in accounts receivables is unfavorable or negative for the company’s cash balance and its liquidity, the $12,000 will be reported in parentheses: (12,000).

-

If the balance in inventory was $250,000 at the end of the year and was $270,000 one year earlier, the inventory had decreased by $20,000. A decrease in inventory indicates that for the year the company did not have to buy $20,000 of the goods that it had sold. This is good for a company’s liquidity. Since a decrease of $20,000 in inventory is favorable or positive for the company’s cash balance and its liquidity, the decrease in inventory will be reported on the SCF as a positive amount: 20,000.

-

If accounts payable had a balance of $60,000 at the end of the current year and was $53,000 one year earlier, it indicates that accounts payable increased by $7,000 during the year. An increase in accounts payable is good for the company’s cash balance and liquidity since less cash was paid out. Since the increase in accounts payable (or other current liabilities) is favorable or positive for the company’s cash balance and liquidity, the increase in accounts payable will be reported on the SCF as a positive amount: 7,000.

From these three examples, you should remember the following when reading the SCF:

- An amount in parentheses is not good, is unfavorable, is negative for a company’s cash balance and liquidity

- A positive amount is good, is favorable, is positive for a company’s cash balance and its liquidity

Operating Cash Flow Ratio

A financial ratio for assessing a company’s working capital and liquidity that is based on the statement of cash flows is:

Operating cash flow ratio = net cash flows from operating activities divided by the average amount of current liabilities throughout the year

Since the net cash provided by operating activities is likely the amount from the SCF of a recent year, it needs to be divided by the average amount of current liabilities throughout the same year. (Using only the amount of current liabilities at the final instant of one or two accounting years may not be representative of the amounts during the year.)

To illustrate this ratio, let’s assume that a company’s SCF for the recent year reported net cash provided by operating activities of $200,000. For the same year it was determined that the average amount of current liabilities during the year was $300,000. Inserting those amounts into the formula, we have:

Operating cash flow ratio = net cash provided by operating activities divided by average current liabilities = $200,000 divided by $300,000 = 67%, or 0.67:1, or 0.67 to 1

Reasons Why Liquidity Will Decrease

Below is a list of reasons why a company’s liquidity may decrease. The list is organized according to the three sections of the statement of cash flows. Since these items decrease the company’s liquidity, they can be thought of as being unfavorable or as having a negative effect on the company’s liquidity. They are also reported in parentheses on the statement of cash flows.

Operating activities

Net loss from the business operations

Accounts receivable increased

Inventory increased

Prepaid expenses increased

Accounts payable decreased

Investing activities

Capital expenditures (purchase of equipment, etc.)

Purchase of long-term investments

Financing activities

Repayment of short-term and long-term borrowings

Declaring dividends on capital stock

Purchase of treasury stock

Draws by an owner

Reasons Why Liquidity Will Increase

The following are reasons why a company’s cash and liquidity could increase. The list is also arranged according to the three sections of the statement of cash flows. Since these items are increasing the company’s liquidity, they can be thought of as being favorable or having a positive effect on the company’s liquidity. The amounts for these items will appear on the statement of cash flows as positive amounts.

Operating activities

Net income from the business operations

Accounts receivable decreased

Inventory decreased

Prepaid expenses decreased

Accounts payable increased

Investing activities

Proceeds from the sale of assets used in the business

Proceeds from the sale of long-term investments

Financing activities

Short-term and long-term borrowings

Proceeds from issuing shares of common and preferred stock

Proceeds from sale of treasury stock

Additional investments by an owner

To learn more about the statement of cash flows see our separate topic Cash Flow Statement.